IWSC Market Insight: the Chinese wine market

Jade Vineyard in China's Ningxia province

- Introduction

- Where do the Chinese buy their wines?

- Where are most wine consumers concentrated?

- Top wine importers in China

- How to get your wine into China

- How do you connect with Chinese consumers?

- Which types of wine are the most popular?

- Domestic wine production

Introduction

In 1996, when then Chinese premier Li Peng praised the health benefits of wine during China’s National People’s Congress, it sent an unmistakable signal to the country’s officials and politically savvy wine merchants: China’s age of wine had come.

That same year, ASC Fine Wines, which would later go on to become China’s biggest wine importer, was created. Wine imports soared; by the end of 2013, the Chinese were drinking more red wine than the French.

That was a generation ago, when China’s wine consumption was not so much about appreciating varietal character but using the liquid, particularly classified Bordeaux, for gifting and to lubricate business meals and banquets.

But the fast rise of wine meant an equally dramatic collapse at the whim of political winds. At the beginning of 2013, Beijing’s new leadership cracked down on luxurious spending and wasteful official banquets; wine sales, particularly of fine wines, dried up. Merchants were stuck with gluts that would take years to deplete.

One of the main impacts of the anti-corruption clampdown is that it accelerated a shift from luxury gifting and prestige-driven wine consumption to more value-driven New World wines. A key beneficiary of this trend is Australia. By the summer of 2019, Australia had overtaken France to become China’s biggest wine supplier, taking up close to 40% market share.

That however did not last long. China slapped a whopping 218% tariff on Australian wines in March 2021, effectively ending Australia’s wine exports to its most profitable market.

There is one thing that is clear about China’s wine market: its boundless promise is matched with equally boundless uncertainty. Although projected to become the world’s second-biggest wine consumer in 2020, China’s ranking in fact slumped from fifth to sixth, a combined result of economic slowdown and pandemic, according to the International Organisation of Vine and Wine's (OIV) latest report on the state of the world viticultural sector in 2020.

Despite Li Peng’s championing of wine back in the 1990s, China’s drinks consumption is still heavily skewed towards baijiu, the ancient grain-based Chinese spirit. Baiju, along with beer, traditional Chinese yellow wine and other spirits, accounts for at least 90% of market share. Post-pandemic, baijiu sales have surged. One explanation is that in uncertain times, consumers lean to what is familiar (baijiu’s origins date back 5000 years).

This is not to say the wine market has no potential. The latest national census shows the country has over 900 million urban residents with high disposable income; there are an estimated 52 million wine drinkers, according to market analyst Wine Intelligence. As Chinese wine consumption moves away from speculative and prestige drinking and becomes more stable as it is taken up by the burgeoning middle class, the wine market size is expected to expand to US$18bn by 2023, up from US$14.8bn in 2018 (Vinexpo and IWSR). China’s vast e-commerce landscape will also have a major role in shaping the future of wine consumption.

It’s worthy to note that Hong Kong, which eliminated wine taxes in 2008, is considered a mature wine market with a large number of experienced wine merchants with specialist knowledge and wine trade experiences. The fine wine trading hub accounts for roughly 60% of global wine and spirits sold at auctions through Sotheby’s, a larger share than London and New York. Across the border in Macau, Portuguese wines remain the most popular wine category thanks to its colonial past. In Taiwan, French wines lead, though wines from the US and Chile are catching up.

WHERE DO THE CHINESE BUY THEIR WINES?

Imported wines take over from domestic

China’s wine market has been slowing down since 2018, a result of the country’s slowing economy and the protracted China-US trade war. The 2020 pandemic significantly complicates this picture.

The country’s imported wine dropped by 27% in value to US$1.95bn (€1.6bn) last year, according to customs data. This is a sharp decline for the second year in a row: the accelerated growth that we have seen in the past seems to have come to an end. It should be noted that compared to domestically-produced wine, imported wine grew markedly from US$2.03bn in 2015 to 2019’s US$2.43bn – even allowing for the distorting effect of the pandemic it was still growing up to 2020.

Domestically-produced Chinese wine - mainly from the country’s two biggest producers, Changyu Pioneer Wine Company and GreatWall Wine – has traditionally dominated the market but the balance has now changed. According to CADA, imported wine has overtaken Chinese wine to be the main category consumed within the country, taking up 60% market share in terms of volume.

Domestic wine production has been on a downward spiral for five years: 2020 production was less than half that of 2016. Data compiled from the country’s 155 leading wineries showed that sales revenue plunged from RMB46bn (US$7.14bn) in 2015 to RMB14.5bn (US$2.25bn) in 2019, according to China Alcoholic Drinks Association (CADA), the country’s official drinks regulatory body.

Overall wine consumption decreases in 2020

In 2020, the country’s overall wine consumption dropped by 17.4%.

The strict lockdown measures in the first quarter of the year certainly played a role. But unlike in the US or Europe, where strong off-trade wine sales helped compensate losses on trade, in China this failed to replicate. The country’s wine consumption is heavily concentrated on restaurants, hotels, bars and other on-trade premises while home consumption was limited.

In China there are over 7.1 million full-service restaurants, 18.2 million fast food restaurants and 404,000 street food stalls, according to 2019 data. In the first half of 2020, restaurants and bars were forced to close or operate within limited hours. In the month of February restaurant and bar closures over Chinese New Year lost wine merchants their most important wine sales period (Chinese New Year wine sales can contribute to as much as 30% of annual revenue for some companies).

5700 bars were forced to close in 2020, according to Chinese research company Zhiyan.

Where are most wine consumers concentrated?

One-third of China’s wine consumers live in Guangdong

China’s 52 million wine drinkers live mainly in the most developed and populous “first tier” cities such as Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou, Shenzhen and Chengdu. Drinkers aged between 20 and 34 are the main drivers for drinks consumption, according to CADA. Guangdong province boasts the country’s highest GDP and with major cities such as Shenzhen and Guangzhou, it is the country’s biggest bottled wine consumer by value, accounting for roughly 30% of the country’s overall wine import value. This is due in large part to residents’ high average disposable income and its close ties with Hong Kong on its southern borders, a mere 50km from Shenzhen.

Data from the Guangdong Alcoholic Drinks Association showed that premium drinks priced RMB600 (US$93) or above generated a total of RMB19bn (US$2.9 bn) in sales last year, a 26.7% increase over the previous year. This was despite months of strict lockdown measures that heavily affected on-trade sales. For bulk wine, Shandong province in eastern China is the biggest market.

HOW TO GET YOUR WINE INTO CHINA

Top wine importers in China

None of these companies – except Changyu Pioneer Wine Company - is publicly listed, so there are no import value/volume figures. The companies are selected based on available logistics data, estimates and operation size.

- ASC Fine Wines

- COFCO Wine and Wine International

- Changyu Pioneer Wine Company

- Torres China

- Summergate Wine and Spirits

- 1919 Wine and Spirits

- Moet Hennessy Diageo

- EMW Wines

There are about 70 wine importers with annual revenues above US$5m. At the time of going to press, data is not available on how many wine importers, wholesalers and retailers survived 2020. According to CADA, there were 6,411 bottled wine importers, but that number shrank to 4,175 within just the first five months of 2019, squeezed by soft consumer demand and a slowing economy.

Given China’s size and scale, there are regional wine importers that focus more on local and regional markets. Beijing Ao Bi An (北京奥比安贸易有限公司) is known for its network in eastern China. Fujian Feng Lian (福建丰联贸易有限公司) in southern China covers an extensive network in affluent Fujian and Shanghai markets. Both are tapped by DBR Lafite as its exclusive distributors for several of its more affordable wine brands. There are specialised wine importers that focus on country-specific wines. There are also recently-founded importers – for example Bruto – which specialise in organic and natural wines.

Aside from importers, supermarkets are another important channel for the country’s wine sales. Yonghui Superstores, Walmart, Vanguard and Hema Superstores (owned by the country’s biggest e-commerce company Alibaba) sell wines ranging from US$5 to over $100 a bottle.

E-commerce has plays an increasingly important part in driving wine sales. A few years ago, only around 5-6% of wines were sold online; this has expanded to 30% today, according to IWSR.

Australian wine exports drop due to tariffs

In the first five months of 2021, as a result of the crippling 218% tariff levied on Australian wines for a five-year period, Australian wine exports to China dropped 81% in value and 84% in volume, bringing its overall market share down to 7% from close to 40%. France has already overtaken Australia to become the country’s biggest supplier, followed by Chile, Italy and Spain, according to the latest Chinese customs data.

Up to this point Treasury Wine Estates (TWE), the parent company of Penfolds and Wolf Blass, had been the biggest Australian wine exporter to China, with AU$1.15bn worth of wines shipped to China in 2020. China represented 30% of TWE’s Group earnings in its fiscal year 2020.

If you look at its star performer Penfolds, the percentage was even higher, with China contributing 39% of Penfolds’ annual global allocation revenue.

Casella Family Group, owner of Peter Lehmann Wines and Yellow Tail, was the second largest Australian wine exporter to China, followed by Australia Swan Vintage Pty Ltd.

French wines doing well

French wines, particularly Bordeaux, have consistently fared well with the country’s fine wine drinkers. Bordeaux became a favourite among wealthy Chinese for gifting and and as a status symbol. By 2009 in the midst of the global financial crisis, China proved to be Bordeaux’s main En Primeur buyer. The En Primeur frenzy though has slowed in the past few years, as the overheated economy cools. Merchants who dived in over the 2009 and 2010 vintages were more cautious with spending amid slowing economy.

Domaine Barons de Lafite Rothschild (DBR Lafite)

Domaines Barons de Rothschild (DBR Lafite), parent company of Bordeaux first growth Château Lafite Rothschild, is another active player in China’s wine market. Not only are its classified Bordeaux wines a favourite among fine wine drinkers, but its Chilean wine Viña los Vascos, and its Bordeaux AOC brands Légende and Saga, and most recently its ultra-premium Chinese wine Domaine de Long Dai are also sought-after.

In particular, wines such as Légende and Saga are formidable volume drivers. When the French wine giant decided to end its exclusive distribution partnership with ASC Fine Wines in 2019 for the two brands, it’s believed the breakup cost ASC 20% of its annual wine sales.

The dangers of fraud

Success in China comes with the danger of fraud. Wines as diverse in price and style as Penfolds (Grange and its high-end siblings), Château Lafite Rothschild and Yellow Tail are frequent victims of copycat wine brands. Intellectual property (IP) infringements became a major headache for companies like TWE and DBR (Lafite), both being mired in lengthy and costly legal battles with trademark squatters and copycats.

Tax cuts on imported wines

Australian tariffs aside, the Chinese government has reduced VAT on imported wines twice in the past three years, from 17% in 2018 to 13% in 2019. For domestic wine producers, it was a different story. Years of lobbying the government to cut excise taxes on domestic wines advocated by the country’s biggest wine producer Changyu and officials from China’s premier wine region Ningxia went unheeded. This is part of the reason imported wines - particularly from Australia and Chile, which both enjoyed zero import tariffs - are often more competitive compared with Chinese wines.

The import tariff remains at 14% and excise tax at 10%. These three taxes combined result in an effective tax rate of 43% for bottled wines and 50% for bulk wine.

HOW DO YOU CONNECT WITH CHINESE CONSUMERS?

The most popular influencers reach millions of wine drinkers

Influencers with millions of followers who can infuse practical information with humour and personality during livestreaming sessions are converting viewership into sales.

In the world of wine, the most influential key opinion leaders (KOLs) are invariably not traditional wine professionals. The country’s top livestreamers are Viya, and Li Jiaqi, who is known as “King of Lipsticks”. Both worked with state-owned Chinese winery GreatWall Winery and sold thousands of cases within a minute.

In the wine sector, the most influential personality is a 32-year-old woman called Wang Shenghan, aka Lady Penguin. Though wine is not yet the main source of her company revenue, her marketing-savvy and video-driven wine content on social media platforms such as Douyin, Weibo and WeChat have gained her millions of followers. On Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, she talks to her more than 3m followers about such things as the difference between a red wine glass and a white wine glass, how to hold a decanter, or how to choose wine based on lipstick colours. She describes the Merlot grape variety as a “friend next door”, and Riesling as a “fairy in a white cotton dress”. Her shop on Tmall.com is frequently ranked among the top 10 best-performing wine stores during the platform’s annual Global Wine and Spirits Festival.

Influencers with a professional wine background

Influencers with a wine education or hospitality background such as Fongyee Walker MW, Edward Ragg MW, co-founders of Dragon Phoenix Wine Consulting, carry serious weight among the more knowledgeable consumer. Julien Boulard MW, fluent in Chinese, specialises in wine education and marketing and runs his wine company Zhulian Wines from his base in southwestern Guangxi province. Gus Zhu MW teaches at Dragon Phoenix. Lu Yang MS, China’s only Master Sommelier, consults for Shangri-la Hotels and Resorts. Lu also founded Grapea & Co, specialising in education and marketing.

Terry Xu, founder of wine consulting company Aroma Republic, is another personality active in the wine scene through education and wine communications. Li Demei, one of the country’s most influential oenologists, dedicates his time to wine education and Chinese wine promotion. There are a few Chinese language wine publications that have built a solid audience, more so than English publications such as Decanter or Wine Spectator. Trade-focused Wine Business Observer (葡萄酒商业观察), Sommelier Magazine(侍酒师画报) and Taste Spirit(知味) are among some of the most read Chinese language wine media within China.

One-third of Chinese wine sales are online

Some 30% of wine sales in China are generated online, a trend driven by tech-savvy millennials and one that is expected to grow.

Today’s Chinese wine consumers are seconds away from connecting with wine merchants. The country has 710m online shoppers, of which 707m are mobile shoppers as of March 2020, a growth that has been accelerated by the pandemic, according to CNNIC.

China’s most popular social media app WeChat, owned and developed by tech giant Tencent, today has 1.15bn monthly active users (in a country of 1.4bn people). Sina Weibo, similar to Facebook, has over 400m monthly active users. Bytedance, the parent company that owns TikTok (or Douyin in Chinese), has some 800m users worldwide. Its competitor Kuaishou, another homegrown video streaming app, has 400m monthly active users.

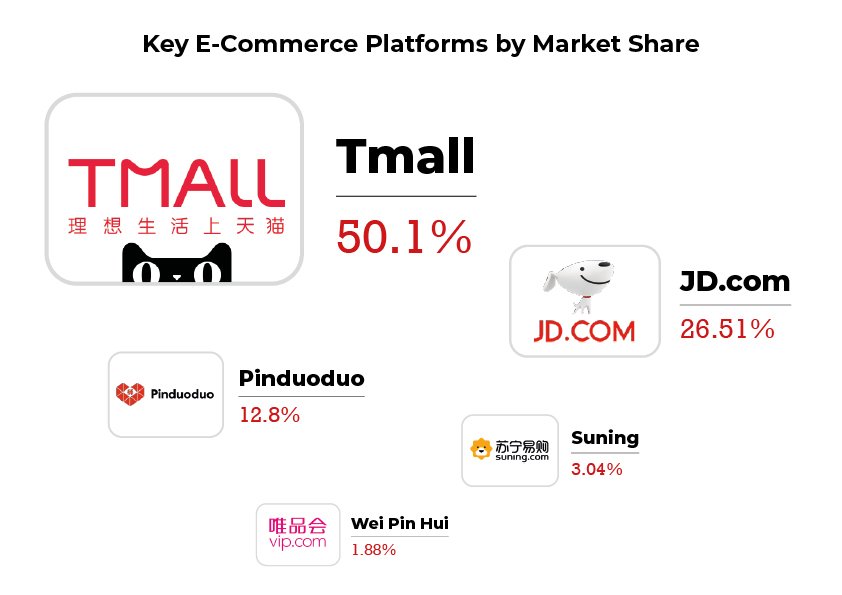

This comprehensive network of Chinese-language social media platforms is intrinsically woven into the country’s leading e-commerce platforms, Alibaba-owned Tmall.com, Tencent-owned JD.com, and Pinduoduo. The three platforms combined would take up close to 90% of China’s overall e-commerce market. The country’s mammoth e-commerce market also spawned a unique and effective selling channel – livestreaming. Alibaba, by far the country’s largest e-commerce operator, and JD.com dominate the livestreaming market with 80% market share.

Source: www.100EC.CN

WHICH TYPES OF WINE ARE THE MOST POPULAR?

In China, wine is red…

In Chinese, the word for “wine” translates as “red wine”. It’s no surprise then that the wine market is heavily skewed towards red; a 2018 Vinexpo report estimated that 90% of the wines consumed in the country are red wines. One of the main reasons for this is the perceived health benefit of red wine; another important consideration is that the colour red, associated as it is with wealth, festivity and power, is auspicious in Chinese culture.

… but white wines are catching up…

As the market matures, shares of white wines, Champagne, sparkling and rosé are expected to grow. Additionally, the low-alcohol category is emerging as a new growth driver. A 2021 report released by AliResearch, the research arm of Alibaba, found the low-alcohol category is gaining ground, driven by female drinkers aged between 18 and 34, most of whom are middle-class office workers, working mothers, and Gen Z consumers.

…driven by female consumers

Off-dry and semi-sweet wines are particularly popular among female consumers in the 25-30 age group, according to CBNData’s young drinks consumer report released in 2020. Sales of dry wines still dominate but off-dry and semi-sweet wines showed the biggest growth online last year. Moscato, as wine merchants would testify, is a crowd-pleaser.

Australia, France and Chile are the leaders in China’s imported wine market, taking up about 70% share. Shortly after the punitive tariffs came into effect on Australian wines, France has reclaimed its top spot as China’s No.1 wine exporter based on Q1 customs data.

Chilean wines are gaining popularity in China. For a long time Chile was propelled by bulk wine exports, which are often mixed with domestically-produced wines. More recently the country’s top brands - Concha y Toro and Baron Philippe de Rothschild’s Almaviva, Don Melchor and Seña - have built a steady following among China’s fine wine lovers. Georgia is picking up wine exports to China, largely thanks to China’s push for the ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative, the ambitious infrastructure project connecting China with East Asia and Europe.

DOMESTIC WINE PRODUCTION

Domestic production is uneven

China’s domestic wine production has been in decline for five consecutive years since 2015. How this sector will develop is uncertain.

The new data shows the country’s production volume at 4.13 million hectoliters in 2020, compared with 4.51 mhl in 2019 - about 35% of the volume of 2015.

One explanation is that low yields and high costs have driven out early investors in the sector. Structural problems such as difficult climate conditions, technical constraints, and low productivity facing wineries are also making Chinese wines less competitive against imported wines.

China’s domestic wine production volume from 2015-2020

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

| 11.6 mhl | 11.3 mhl | 10.01 mhl | 6.29 mhl | 4.51 mhl | 4.13ml |

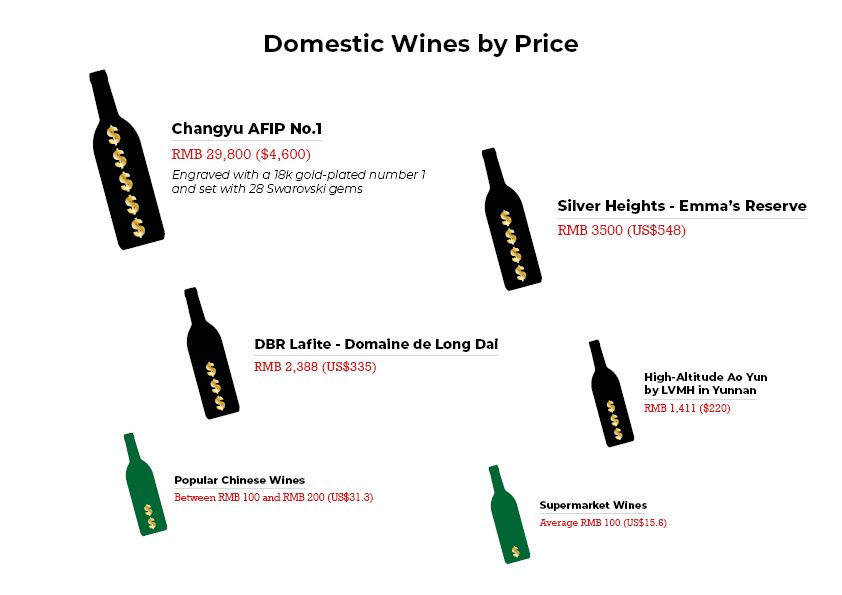

There is a very wide variety of Chinese wine. Mass wines churned out in coastal Shandong province can sell for US$2 a bottle or less. Most of the wines hitting supermarkets are priced around RMB100 (US$15.60) a bottle, from the country’s biggest producers such as Changyu Pioneer Wine Company, GreatWall Winery, Dynasty and Weilong Winery.

Higher quality wines from Ningxia average around RMB300 (US$46) a bottle and are gaining popularity among the country’s younger consumers who take pride in well-crafted Chinese products. Collectibles from some of the country’s top wineries such as Silver Heights’ Emma’s Reserve can go up to RMB 3500 (US$548) a bottle.

There’s a shift to making low-intervention, organic, biodynamic and natural wines among China’s top tier wineries in Ningxia and Xinjiang. There is also a gathering movement amongst the world’s major fine wine groups to tap into China.

DBR Lafite’s Chinese winery Domaine de Long Dai released its Bordeaux blend first vintage, the 2017, with a whopping price tag of RMB 2,388 (US$335) a bottle, similar to the price for high-altitude Ao Yun by LVMH in Yunnan. There’s also no shortage of Chinese producers making surprisingly pricey wines in heavy bottles with high-concept (and arguably pretentious) packaging. Changyu AFIP No.1, engraved with a 18k gold-plated number 1 and set with 28 Swarovski gems, sells for RMB 29,800 a bottle.

The country’s biggest wine producer is Changyu Pioneer Wine Company, headquartered in Yantai, Shandong province. Its annual production is around 200m litres, and it has expanded its production to Ningxia, Beijing, Liaoning, Shaanxi, and Xinjiang. The listed wine company has also snapped up vineyards in Spain, Chile and Australia, with much of the output destined for China.

State-owned GreatWall Winery is the second-biggest wine producer in the country. Similar to Changyu, it has wineries in Ningxia, Hebei and Shandong.

Other notable Chinese wineries that are building a steady following are Silver Heights, Legacy Peak, Tiansai Vineyards, Puchang, Grace Vineyard, Xige, Domaine Franco and Domaine des Arômes.