IWSC Business Insight: Berkmann Wine Cellars

Founded in 1964 by Joseph Berkmann

“A personal touch”

Italy, Burgundy, California

79% on-trade, 21% off-trade by value

How to differentiate

“Being interesting is as valuable as being cheap”

“On the knife-edge between the creative and the commercial is where the magic happens”

“Think change”

Tell us about the company background.

The company was founded in 1964 by Joseph Berkmann, who started importing wines for his group of London restaurants. Before long, other restaurants looked to benefit from his taste and expertise, and the company began to grow. BWC began adopting an agency model in 1972, taking on the UK exclusivity for Georges Duboeuf. In 1987, BWC expanded into the North of England, and has since broadened and diversified, becoming a fully-fledged agency house delivering nationwide to all channels of the UK trade. In 2012, the reins were passed to the second generation, Rupert Berkmann, who set up subsidiaries BWC Brasil and Spirit Cartel.

What's your USP?

BWC is unique these days in being a family-owned, family-run wine distributor of scale. That may sound like an academic point, but it’s not. The advantages are, in no particular order:

- Stability of ownership = one less thing for management to be distracted by

- No plans to sell = no need to grow aggressively at any cost

- Independence and neutrality: no preferential treatment of certain suppliers or other stakeholders

- A personal touch: people can meet Rupert at tastings, supplier meetings etc; the team know who they are working for. This helps encourage drive and foster confidence in the business

- Generational timescale + flat hierarchy = long-term thinking coupled with rapid decision-making

- A natural affinity with family-owned wineries of any scale – be it Coche-Dury or Antinori, they think in similar terms to us

BWC is also unusual in having such even national coverage. It’s not a London merchant with a few regional reps – or vice versa – and we are not beholden to courier companies. Our own vans deliver throughout GB, and a balanced 35% of our on-trade sales force is London-based.

I can’t think of another company with such breadth and diversity of portfolio yet a relatively compact list (ca. 1400 lines). We have wines from 22 countries featuring 170 grape varieties, with many leading names in their respective regions. Price point ranges from £5.60 to £3,500 dpd ex-VAT, and the producers are anywhere between 15,000 and 25m bottles per year. Yet despite all this, the range is of a manageable size and even maintains a certain house style. (BTW it is possible to have a Michelin star, BWC as sole supplier, and still win awards for your list!)

How are the products evolving?

I guess Spirit Cartel itself doesn’t count as new anymore, but they do have new products this year (e.g. Bobby’s Gin, Copperhead Gin, Westward American Single Malt Whiskey, Worthy Park Rum).

Recent BWC additions include:

(2020) Brash Higgins, Xavier Monnot, Tbilvino, T-Oinos, Librandi, Tenuta San Leonardo, Château Ksara, Sevilen

(2019) Tournon (Chapoutier), Yarra Yering, Château Minuty, Domaine Bernard-Bonin, Domaine of the Bee, Ca’ del Bosco, Umani Ronchi, Viñas del Cámbrico, Soto Manrique, RAR, Belarmino

Strengths are Italy, Burgundy, California.

What is the breakdown by sector?

Pre-Covid split was 79% on-trade, 21% off-trade by value. This strong bias towards the former is because on-trade was the main channel of growth in the last five years, during which BWC doubled its turnover.

What have been some of the challenges?

The global financial crisis of 2008/09 is an obvious one, although no less challenging for that! We were faced with a tough strategic decision as confidence drained from the market while the pound deflated: join the race to the bottom, or stand by our quality standards and ride the situation out. That we opted for the latter should come as no surprise, but at the time it took a lot of debate to become confident in maintaining our stance as the ground shifted under us.

The other, related challenge is a more perpetual one: one of our stated aims is to make a profit, yet we are obliged to compete with businesses for whom there are other priorities, and who have therefore eroded margins across the industry. This entails a secondary challenge: how to differentiate, which as a distributor is not always evident.

What have you learnt from overcoming those challenges?

That there is always a market for quality.

That adapting to market conditions mustn’t compromise your values.

That with 1% market share, we can swim against the tide of macro trends.

That customers who obsess over price above all else have poor long-term prospects.

That value inheres in both the wine itself and the extended service we provide (delivery, training, design, advice, marketing support, etc).

That being interesting is as valuable as being cheap.

That consumers look for an experience they can value when they go out – if they just wanted to save money, they’d stay at home.

That partnerships (with both customers and suppliers) are more important than transient deals.

What advice do you have for young wine producers, for distributors - for anyone wanting to get into the logistical side of the wine trade?

From whatever angle you approach it – production, distribution or retail – working with wine requires an acute and sometimes contradictory combination of romantic sensibilities and business acumen. The reason is that wine is an alluring and therefore highly competitive field, full of passionate people against whom it takes a great deal of flair and imagination to compete. Yet as a sector with often slim margins at every stage of the supply chain, the commercial and financial angles have to be expertly covered too. And finally, in such a crowded space, gap analysis and genuine differentiation are vital.

We see wine companies start with a dream but no business plan, and others that are thoroughly costed but deathly dull. Both types risk sinking without trace, as do those who replicate an existing proposition in the market. On the knife-edge between the creative and the commercial is where the magic happens.

Preparing for the next generation - how can you future-proof the business?

The first step is, as Joseph Berkmann always advises, “think change”. This doesn’t mean we follow every fad that pops up – rather, we subtly and continuously evolve according to shifts in demand as well as preparing for future opportunities.

Some short-range examples: as a Burgundy specialist, we have witnessed the huge surge in demand and diminishing crop size in the last decade. Prices have doubled, allocations are smaller, and climate change may be coming into play too, with back-to-back scorchers in 2018 and 2019. We’ve therefore taken a position in premium California, which is arguably better positioned to deliver a stable supply of cool-climate terroir-expressive Pinot Noir well into the future, and is certainly offering gentler prices than Burgundy already.

If climate change does start to have a dramatic impact on wine styles and availability, then companies like ours will play an important part in understanding the shifts, sourcing from new regions, and communicating the stories clearly to a fairly traditionalist market with limited bandwidth for the complexities of wine.

If the trend to drinking less alcohol continues in the UK, we need to ensure our premium message is getting through, and that people who drink less drink better, thus retaining value in the industry.

Spirit Cartel has been sensitive to the modulation in tone in the cannabis vs alcohol discussion, and so has been swift to add a CBD drinks brand to its portfolio.

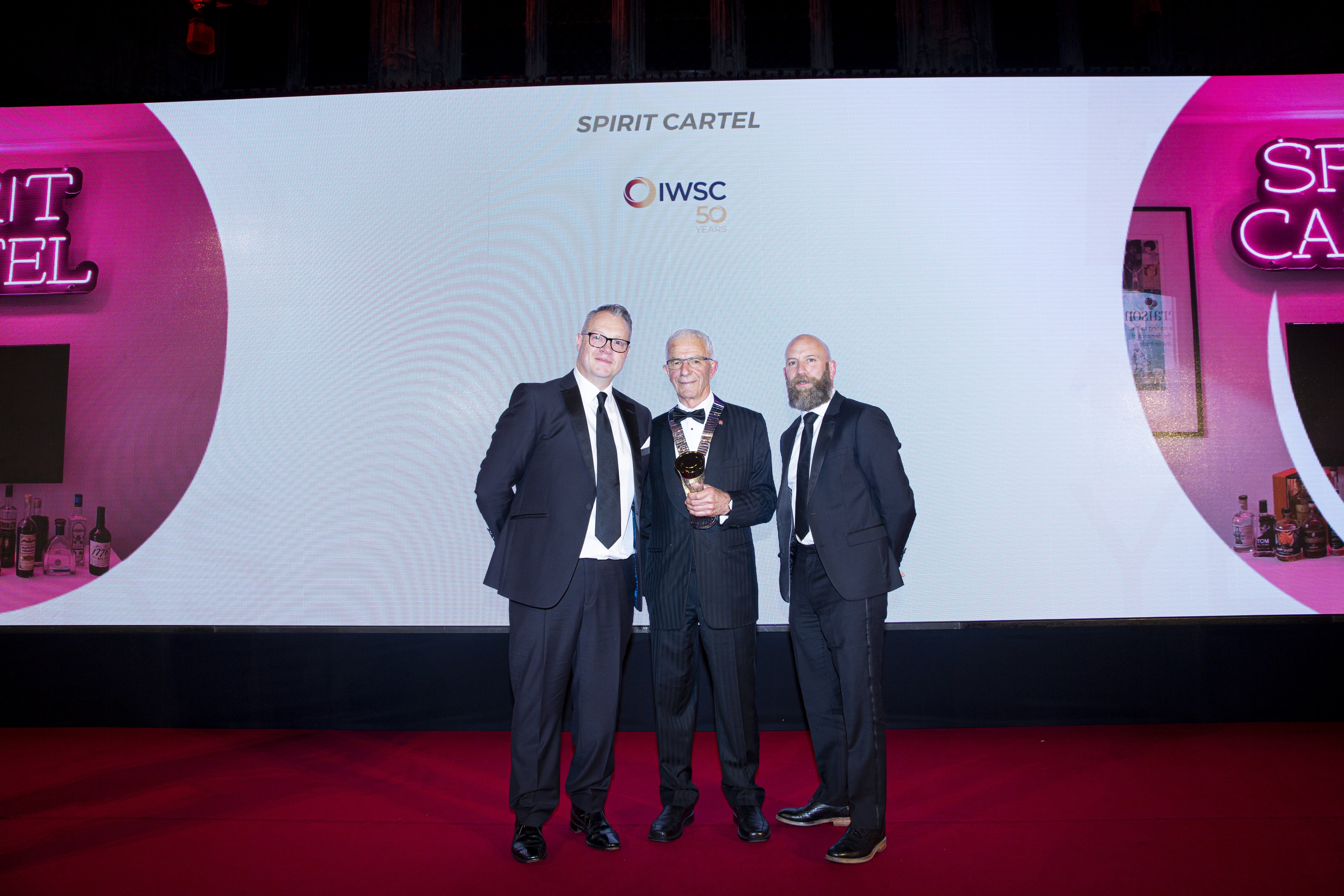

Spirit Cartel was awarded IWSC Spirits Distributor of the Year last year

Longer-term, it is almost certainly going to be technology that will be the most powerful force shaping our business. Wine’s great strength, and great weakness, is that it is a finite physical product. A bottle of wine is heavy and fragile, requiring high energy input to produce and transport. Non-destructive sampling is impossible. Other than in cases of intricate physical counterfeiting, it is piracy-proof. Supply and demand influence price. Contrast this with the media we consume every day – digitally encoded, instantly accessible, infinitely sampleable, piracy-prone, flat-priced…

Wine is still in a pre-Edison state, which is unlikely to last forever. Physical synthesis – lab-produced “copycat wine” – is already in its infancy. The technology to encode, transmit and reproduce smells, tastes and textures is decades away, and may require sophisticated computer-brain interfaces to bypass the physical senses before it’s viable, but long-term seems inevitable.

Where does that leave the wine business? At the moment, the physical constraints are largely responsible for the ‘content’ – the biochemistry of grape varieties and their interaction with terroir provides the majority of the flavour nuance, and there is no way we could have created such wonders from first principles. But if wine dissociates from agriculture and mutates into some sort of digital essence, our logistics will not be necessary, while our content curation will be just as relevant as now.

And perhaps there will be even more value attached to real, physical bottles of wine for a special occasion – authenticity and transience have an enduring allure. After all, who could have predicted in the age of Netflix and Spotify, that theatres and concert venues would be so full? Until the virus hit of course…

That alone has taught us the future is unpredictable, and that alertness, flexibility and resilience are what will help us survive.